Investing in pure research is unpredictable but essential

This oped was published in the Edmonton Journal on November 18 and in the Lethbridge Herald on November 21, 2017

By Mike Mahon, Universities Canada chair and president of the University of Lethbridge; Elizabeth Cannon, Universities Canada past chair and president of the University of Calgary; and David Turpin, Universities Canada board member and president of the University of Alberta.

Where will the next important research breakthrough come from? How will it revolutionize the way we live? It is impossible to predict. We can only be sure of where the journey begins: with a curious researcher testing and analyzing new, untried ideas and theories.

Fundamental research — research that has no immediate goal — underlies every great invention and every great economic change. It’s risky and unpredictable but it’s essential to the future.

When the federal Fundamental Science Review panel issued its report in spring 2017, our beliefs were confirmed regarding the steep decline in Canadian research competitiveness.

As we look for ways to turn innovations into marketable products and services, we know we have the support of government through programs and organizations such as Canada’s Innovation and Skills plan and Alberta Innovates. They help accelerate innovation and promote Canada as a global leader. They also expand the capacity of universities to train students to join a highly qualified workforce in emerging industries.

But we must not lose sight of the importance of funding fundamental research, the starting point for any important breakthrough.

Innovation is driven by curious people asking challenging questions. Finding answers usually takes years of dedicated scientific inquiry. Often, they find solutions to questions they didn’t even know to ask.

At the University of Calgary, engineering professor Ian Gates wondered if there were better ways to upgrade bitumen from oil sands. His team’s experiments led to a seemingly unusable product: bitumen pellets, ranging in size from a golf ball to a pill. Gates put his results on the shelf and moved on.

Then, with companies struggling to build pipelines, Gates realized his discovery could open a marketable method of cheaply and safely transporting Alberta’s oil reserves by rail. The bitumen balls vastly reduce the chance of a spill and subsequent damage to the environment. Gates has patented the discovery, partnered with Innovate Calgary to commercialize it, and will pilot the project this fall.

Similar unexpected discoveries in social sciences and humanities can provide huge social benefits that improve the way people live, work and learn.

In 2014, the Alberta government used the Early Development Instrument (EDI) to determine how prepared children were for kindergarten. The study revealed Alberta children were below the Canadian average. At the same time, Robbin Gibb, Claudia Gonzalez and Noella Piquette, and an interdisciplinary team in neuroscience, kinesiology, and education at the University of Lethbridge, discovered a link between key cognitive abilities and hand preference for grasping.

Children who prefer using one hand over the other have better cognitive control of behaviour. They also have better language reception and production skills. These discoveries led to a program now offered in preschools and daycares in southern Alberta, to improve children’s executive function through physical activity. The goal? Children being better prepared for kindergarten and future schooling

When a discovery is announced, the initial reaction can be: what is it good for? The reality is that not all fundamental research immediately contributes to economic prosperity or physical well-being. The process of discovery is often incremental.

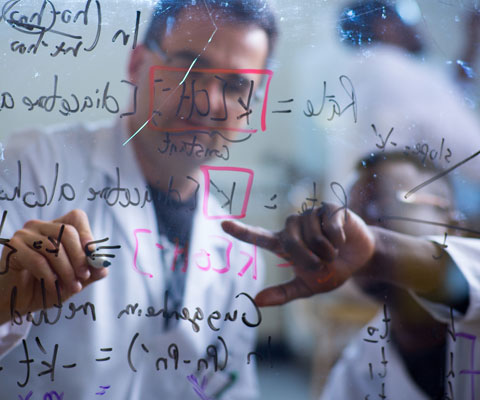

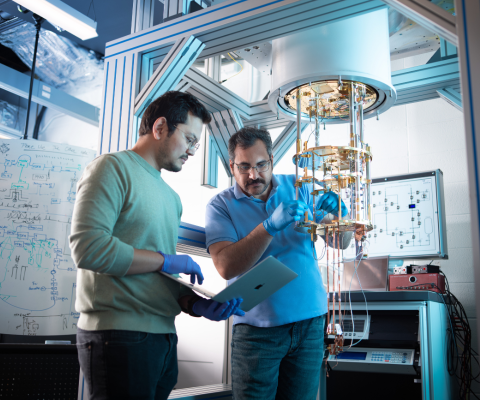

In the 1950s, Japanese physicist Leo Esaki first observed an electrical phenomenon known as negative differential resistance (NDR), which led to the creation of the Esaki tunnelling diode, the first quantum electron device. Its commercial potential was never fully realized because no one could control the unpredictability — until now.

Earlier this year, physicist Robert Wolkow and his team at the University of Alberta determined the atomic structure that generates NDR and how to control and replicate the effect within atoms. They developed techniques to create atomic-sized electrical circuits. These discoveries — based on decades of fundamental research — have the potential to revolutionize electronics through commercial development of ultra-fast and low-power quantum computers.

Curiosity and research matter. When researchers collaborate with entrepreneurs and industry partners, the journey of discovery transforms into something more. Technical innovations, data for future studies, solutions to challenging problems, new jobs — these are just a few of the social and economic benefits.

This is why we need to invest broadly in fundamental research. This isn’t research for the sake of research; it’s human exploration for the benefit of all.

-30-

About Universities Canada

Universities Canada is the voice of Canada’s universities at home and abroad, advancing higher education, research and innovation for the benefit of all Canadians.

Media contact:

Lisa Wallace

Assistant Director, Communications

Universities Canada

[email protected]

Tagged: Research and innovation

Related news

-

Urgent action for our publicly-funded universities critical to Canada’s economic stability and growth

-

Outstanding discoveries by Black researchers in Canada

-

Universities are advancing technology through international partnerships

-

Global university partnerships are finding solutions to the climate crisis